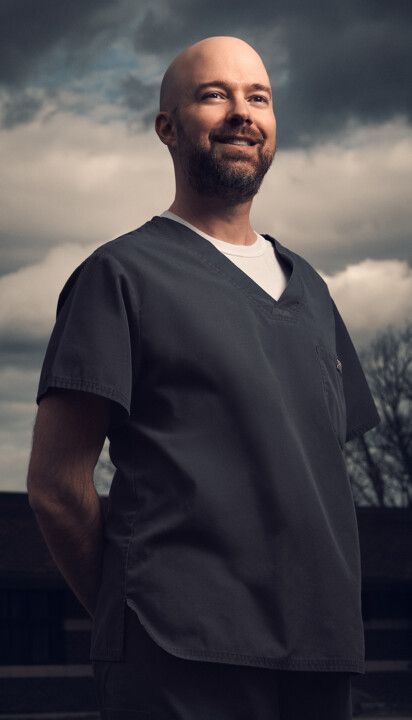

Buffalo-area public-health dentist Dr. Alex Campagna first came to wide notice with a high-spirited, neighborly Good Samaritan act this past Christmas. His turn as an accidental hotelier was dramatic, but it turns out that helping people is a core aspect of his personal and professional lives alike.

IT SEEMS LIKE a pretty good bet that by now you’ve heard the heartwarming holiday tale—not yet a Hallmark Channel movie, but give it a year—of Dr. Alex Campagna. Last December, amid a ferocious blizzard in the Buffalo, New York, area, the dentist and his wife, Andrea, ended up hosting 10 stranded South Koreans at their home in Williamsville for two days over Christmas.

The improbable saga began around 2 p.m. on Friday, December 23, during what New York Governor Kathy Hochul called the “blizzard of the century.” Snow had been falling in torrents for two hours when two men, dusted in flakes from head to toe, knocked on the Campagnas’ door asking if they could borrow a shovel or two to dig their party out.

The duo were part of a group of Korean tourists whose van had become stuck near the Campagnas’ driveway as they headed to Niagara Falls. Recognizing immediately that the travelers wouldn’t get far even if they freed their van, the Campagnas didn’t think twice about inviting the group inside. “Our guests were anxious and wet from the snow, but otherwise they were healthy,” says Dr. Campagna, 40. “My wife—who’s a surgical nurse practitioner—and I used our experience and

reassuring bedside manner to help these people feel comfortable and tend to their immediate needs.”

“It’s difficult for me to articulate how honored we feel to have welcomed these people into our hearts.”

After a quick, respectful medical evaluation, the Campagnas got to work, serving freshly brewed coffee and Christmas cookies, and passing out blankets and socks to ensure that their unexpected visitors—seven women and three men—would be warm and comfortable. (Three of the Koreans spoke decent English, which helped with the cross-cultural exchanges.)

While snow continued to fall, the Campagna home became a hive of activity. What unfolded over the next 37 hours—luckily, they never lost power—would earn Dr. Campagna a new title on his already impressive résumé: accidental innkeeper.

Hunkering down, the couple and their guests prepared home-cooked meals, including a number of Korean staples.

(In a perfect holiday touch, the Campagnas have long been enthusiasts of Korean cuisine; the tourists were delighted and amazed that their hosts had all the necessary ingredients already on hand.) They broke out the bubbly to toast a newly married couple in the group and watched wildlife navigate the backyard. They shoveled nearly four feet of snow like a miniature army and then thawed out in front of the TV, watching the Buffalo Bills clobber the Chicago Bears, 35-13—a fitting introduction to football for their new friends.

Eventually the snow abated and the first plow charged down the Campagnas’ street; the out-of-towners were finally on their way by 6 p.m. Christmas Day. “The Korean guests demonstrated such gratitude, bonding with us over this destructive experience caused by Mother Nature,” Dr. Campagna says. “It’s difficult for me to articulate how honored we feel to have welcomed these people into our hearts.”

The couple’s hospitality (and well-stocked kitchen) offered both them and their guests a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It was all of a piece for Dr. Campagna, a longtime Buffalonian whose good nature and easy charm go deeper than the drifts outside his home that eventful weekend.

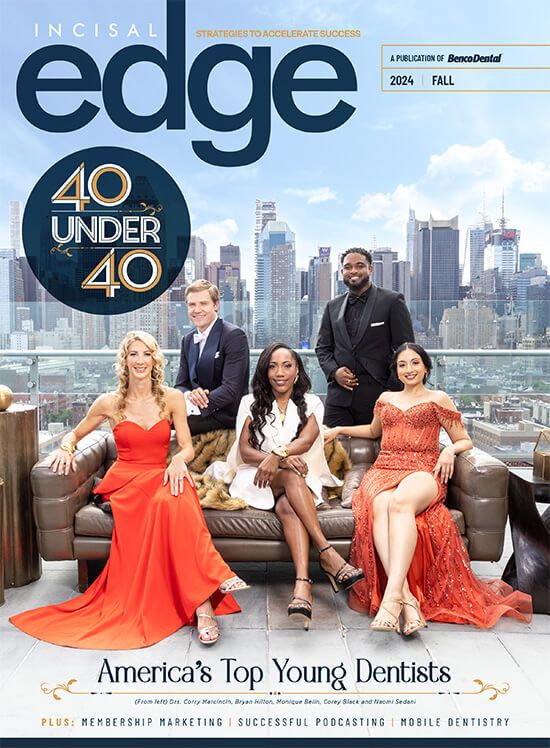

BUFFALO SOLDIERS: Dr. Campagna and his wife, Andrea (center), receiving a medal in recognition of their generosity from New York Governor Kathy Hochul

AN ETHIC OF SERVICE

Since 2011, Dr. Campagna has worked as a dentist for the Seneca Nation Health System (SNHS), a public-health network that provides comprehensive services to eligible Native Americans across rural western New York and northwest Pennsylvania.

Part of the Indian Health Service (IHS), the federal agency that provides medical care to 2.6 million indigenous Americans, SNHS sees between 12,000 and 14,000 patients every year. “Since the Seneca Nation Health System is not just a dental clinic, patients can call it their health care home,” Dr. Campagna says. “They have access to medical, dental, optical, pharmacy and wellness services, all under one roof.”

The majority of SNHS patients are members of the Seneca Nation of Indian Tribes, one of the tribes that make up the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. (American schoolchildren learn how the Founding Fathers borrowed from the organizational structure and policies of the five Iroquois tribes when they were drafting the U.S. Constitution.)

SNHS’s lauded dental program provides comprehensive and emergency dental care and education to adults and children throughout the Seneca Nation, which has a population of about 8,000. “[Public health] is kind of in the background when we think about dentists,” Dr. Campagna says. But the goal of public health is anything but insignificant: to provide quality care to the greatest number of people, including those who can’t afford or don’t have access to dental care. “Data surrounding patient care is studied seriously with new approaches tailored to individual native communities—trying to benefit the most amount of people—being developed and implemented continuously.”

SNHS dental runs two clinics in Irving and Salamanca, New York, on the Cattaraugus and Allegany Territories, respectively. The program follows a three-pronged approach that includes oral-hygiene instruction, preventive care and individual treatment plans. One primary focus is educating children and their families about the importance of dental hygiene through community outreach, such as handing out toothbrushes and pamphlets at local events. The need is acute: According to the National Institutes of Health, Native American adults have double the prevalence of untreated dental caries and higher chances of having severe periodontal disease, missing teeth and oral pain.

The program also prioritizes early intervention, providing off-site dental exams for kids in the Seneca Nation’s child care program. “The earlier the intervention to help parents and children have an understanding of nutrition, keeping their teeth clean, home care and the importance of checkup appointments, the better,” Dr. Campagna says.

“Once the patient enters our system, the majority of their needs can be addressed, as opposed to in a private practice where patients probably have multiple providers spread

over multiple offices with different disciplines.”

Several clinic team members are themselves part of the Seneca Nation and live in the community, which Dr. Campagna says has helped spread awareness and bring patients through the doors: “It demonstrates confidence to the community that family members and neighbors will receive high-quality care delivered compassionately because of the mutual trust between the patients, administration and [providers].”

Public-health dentistry’s lower profile, he adds, leads to some misconceptions, starting with people’s often erroneous notion of the professionals who choose to work in the sector. “I’ve found that some of the best dentists and dental providers work in public health,” he says. “Patients come to appreciate that they aren’t treated in assembly-line fashion and there’s no hard sell of any products or services.”

Additionally, the tribally administered program’s affiliation with the federal IHS means its providers must adhere to rigorous guidelines. “Dentists are held to a high standard and subject to periodic comprehensive reviews of their work through IHS, which helps providers improve and refine their skills,” Dr. Campagna says. Case in point: The SNHS dental clinics earned the IHS’s “Most Improved Clinic” award in 2012, followed by “Clinic of the Year” in 2013, both coincident with Dr. Campagna’s arrival—a steady upward trajectory that has only continued in the decade since.

Another misconception about public-health dentistry, he says, concerns the instruments and supplies available to such clinicians. These are hardly leftovers from private practices. “We use high-quality materials, often out of the reach of the budgets for basic private practices, and our equipment is serviced regularly.”

He cites as well misunderstandings about how long patients must wait for appointments. SNHS clinics prioritize emergency and urgent care via a scheduling system implemented two decades ago by Dr. Joseph Salamon (who still works there) and now overseen by clinic manager Sharri Henhawk. “If a patient calls with pain or an acute infection, they’re seen [quickly] without disrupting the flow of scheduled patient care,” Dr. Campagna says.

As in a private practice, working in a public-health clinic has advantages and challenges. The biggest challenge, he says, is access to care, which can mean “simply transporting or even convincing people to walk in the door.” A primary benefit, though, is the way the clinic helps improve the patient experience and continuity of care. “Once the patient enters our system, the majority of their needs can be addressed, as opposed to in a private practice where patients probably have multiple providers spread over multiple offices with different disciplines.”

Working in public health, he adds, enables him to stay connected to his patients over the long term. “In private practice, maybe a patient ends up moving or going to a provider down the street and you never hear from them again. Through the bigger system, it’s easier to follow a patient’s care.” Likewise, the fact that patients aren’t financially responsible for the services takes certain difficult conversations off the table. For example: “ ‘I know you’re in pain; however, it’s going to cost you X to get you out of pain,’ ” he says, imagining such awkward hypothetical encounters. Or “ ‘Remember when you were in last month? Well, your insurance denied the claim, so you owe us X amount.’ ”

DEDICATION FOR LIFE

Helping otherS IS a thread woven throughout Dr. Campagna’s life. Born in Grimsby, Ontario, he moved with his family a handful of times before they settled in the United States in a Buffalo suburb called Lockport in 1995, when he was in middle school. His social skills blossomed when he was a teen and became accustomed to making new friends with ease. “I knew I wanted a career where I could interact with lots of new and different people,” he recalls.

He was drawn to dentistry throughout, from getting fillings in high school from his hometown dentist, having his wisdom teeth extracted by the local oral surgeon and logging hours at the orthodontist when braces came calling. When he was an undergraduate at the University of Buffalo, that hometown dentist, Dr. Joseph Shaw, graciously let Alex shadow him at his private practice—an experience that solidified his desire to apply to dental school. He enrolled in the University of Buffalo School of Dental Medicine, earning his DDS in 2009. He then completed a residency at Buffalo General Hospital. After joining SNHS, he won the National IHS Junior Dentist of the Year Award in 2015.

These days in the clinic, he provides dental treatment, including direct and indirect restorative care, and emergency treatment. His favorite interactions, though, are when he gets to relieve his charges’ pain. “I get a lot of satisfaction when I know my patients are feeling better.”

He helps oversee the IHS externship program at SNHS, which hosts fourth-year dental students from various accredited schools around the country, and he works to sell them on a career in public health. “I’ve tried to instill in these students there are other opportunities to help patients outside the private practice model.”

His professional routine has been a constant for years. Every Tuesday through Friday, he’s up and out the door before dawn to make the 43-mile (one way) commute from Williamsville to the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation Health Center in Irving. And though much of his daily work can be ordinary, it never gets old. “I’ve known my patients for 12 years, so it’s fun to catch up when they’re in the chair.”

The feeling appears to be mutual. Dr. Campagna’s patients routinely bring him vegetables from their gardens, fresh baked goods and homemade sauces. One woman sends him postcards when she travels; he recently received one from her from Alaska. “Over the years I’ve collected many notes from patients expressing gratitude for the care they received or catching me up about their lives,” he says. “I’ve received gifts that have native symbols on them. And that means a lot to me, reinforcing that this is a unique culture I would not have been as aware of had I not been working in this community.”

The people in his chair are much more than patients. They’re the heart and soul of the community he’s been providing care to for more than a quarter of his life. “This is a community that places family values at their core, supporting neighbors and loved ones in difficult times,” he says. “And you can imagine that has to do with the weather conditions we deal with.”

And so the good doctor comes full circle. He could just as easily be describing the animating values of himself and his wife, which meant the generosity they displayed toward the stranded South Koreans during that treacherous winter storm was second nature. Since then, the couple have received an outpouring of su pport—not only from Dr. Campagna’s patients and SNHS colleagues, including a recognition event organized by the health system’s CEO, Shaela Maybee, but from the Seneca Nation of Indians as well. “I’m so proud and honored to be recognized by this community,” he says. “I have a true feeling of belonging.”