One day last year,

Dr. John Tucker, of Tucker Educational Excellence in Erie, Pennsylvania, received a custom pen-and-ink drawing of a lighthouse near his practice. The gift was from Sue Peters, a 73-year-old patient of Dr. Tucker’s, who attached a note that read, “Thank you for giving me my life back.”

Today, more than at any time in the past, sleep apnea is recognized as a dental problem in addition to being an ailment of the airway per se. It’s a common (yet serious) disorder that causes one’s breathing to become shallow or stop completely during sleep. This breathing caesura—called “apnea”—can last 10 seconds or more and happen more than 30 times an hour, prompting a serious reduction of oxygen in red blood cells and even more deleterious potential effects on long-term health.

Remarkably, not a single organ in the body is unaffected. Sleep apnea’s comorbidities—ailments that often accompany it, to an individual’s great detriment—include hypertension, high blood pressure, stroke and Type 2 diabetes; it has recently been linked as well to cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, even gout. Alarming stuff—yet some 93 percent of women and 83 percent of men (out of the estimated 30 million Americans who suffer from the condition) haven’t been clinically diagnosed. What gives?

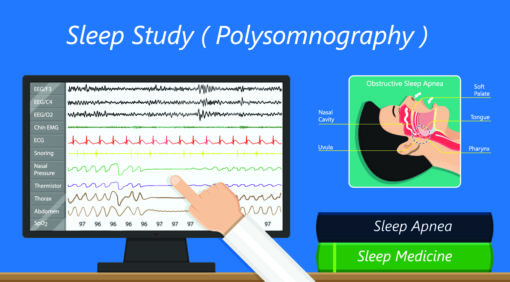

WELL, FOR ONE THING, the very process of diagnosis has been cumbersome for years. Aside from a physical examination, sleep physicians typically recommend a sleep study (polysomnography)—which is sometimes done at home by more often during an overnight stay at a sleep-study clinic. It monitors blood oxygen, heart rate, brain waves and periods of breathing pauses via sensors on the scalp, temples, chest and legs. Add to that the prospect of potentially being bound for life to a CPAP machine—an air pump that fills the lungs with air, the leading therapy for sleep apnea since the early 1980s—and patients have been scrambling to their dentist’s office for alternative options.

According to a recent article in CHEST, the official journal of the American College of Chest Physicians, one in four dental patients present symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea, and (believe it or not) people are more likely to see their dentist regularly than their general physician. That’s where clinicians like Dr. Tucker come in.

“Most patients spend at most 10 minutes with their primary-care physician,” he says. “Dental practices take pride in how much time they spend with them.”

In October 2017, the American Dental Association adopted a policy concerning dentistry’s role in screening and treating patients for sleep apnea. Its key components include assessing an individual’s risk via a comprehensive medical and dental history, and providing OAT when a patient can’t tolerate a CPAP device for whatever reason. “Dentists are the only health-care provider with the knowledge and expertise to provide OAT,” the ADA’s policy stressed.

Unlike CPAP, which involves a full-face mask and a generator, OAT works via a device that simply pushes forward the mandible, which tends to fall back during sleep, causing the tongue and other tissue to obstruct the airway. “The industry standard is that 50 percent of patients diagnosed with sleep apnea can’t tolerate CPAP therapy,” Dr. Tucker says. “It’s not very comfortable. I suffer from sleep apnea and couldn’t tolerate [CPAP]—that’s one of the reasons I got involved with [OAT].” He’s just one of many dentists nationwide who have dedicated time, energy and research to CPAP alternatives. “It’s about letting the ‘sleep community’ know that we want to be a part of the treatment of the patient.”

Broadly speaking, the dental industry’s initial involvement with sleep apnea arose from an interest in occlusion and devices to counteract teeth grinding by moving the jaw forward.

“We saw that there was a connection between that and the airway, but unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of communication between the dental and medical field, so CPAP got to be the treatment of choice because it was the existing technology of pulmonologists,” says Dr. Richard Anderson, who for nearly 35 years has practiced orthodontics at Anderson Dentalcare in Minneapolis. “Physicians are [now] becoming more aware of what dentists can do, and dentists are seeking MDs who are interested in this area.”

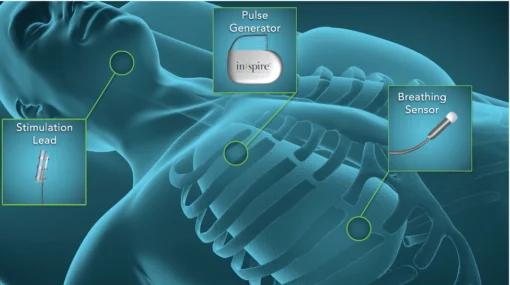

Inspire Upper Airway Stimulation Therapy, developed by Inspire Medical Systems, a technology company in Maple Grove, Minnesota, is a device comprising electrodes that’s implantable in the muscle that controls the tongue and prevents it from relaxing, drifting back and blocking the airway during sleep. The stimulation is so slight that patients don’t feel it. ( Photo courtesy Inspiresleep.com )

RECOGNITION OF mutual interest between physicians and dentists has led fitfully to other, surgical approaches, such as laser therapy aimed at decreasing the volume of tissue in the soft palate, removal of the tonsils and even uvulectomy, in which all or part of the uvula is taken out. None has found much purchase.

Perhaps the strongest technological advance of late is Inspire Upper Airway Stimulation Therapy, developed by Inspire Medical Systems, a technology company in Maple Grove, Minnesota, just outside Minneapolis. It’s a device comprising electrodes that’s implantable in the muscle that controls the tongue and prevents it from relaxing, drifting back and blocking the airway during sleep. The stimulation is so slight that patients don’t feel it. What they do feel is its cost: $40,000, prompting questions about whether insurance might cover it (most plans don’t) and, perforce, accessibility.

Not all sleep apnea, it turns out, is created equal. And that’s where Vatech’s new i3D Premium Intraoral Imaging System comes in. It’s the latest sleep-specific product from the Fort Lee, New Jersey–based leader in dental imaging, and it offers welcome precision when a dentist is trying to pinpoint the exact obstruction problem.

“What we’re finding is that this space of closure in the airway isn’t always in the same area,” Dr. Anderson says. “Vatech assesses the airway and allows us to see quite dramatically where the space of contact is. In some cases, it’s farther down than what you can advance with the lower jaw, so OAT isn’t going to work for that.”

Vatech’s new i3D Premium Intraoral Imaging System is the latest sleep-specific product from the Fort Lee, New Jersey–based leader in dental imaging, and it offers welcome precision when a dentist is trying to pinpoint the exact obstruction problem. ( Photo courtesy VatechAmerica.com )

Ortho specialists like Dr. Anderson, as such, are turning their attention to intercepting the problem rather than focusing on treating it down the road. A number of studies published in recent years by the ADA have found that adults who have had teeth removed for orthodontics are more likely to encounter trouble with sleep apnea, as are children diagnosed with behavior- and focus-related Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, all of which might simply be rooted in having trouble sleeping because of airway blockages.

“When you take teeth out, you need to take whole units—so then you’re left with way more space than you needed to correct the problem,” Dr. Anderson says. “Then you’re left with pulling teeth back and making the arch of the mouth smaller.” The norm in orthodontics used to be to wait until kids’ teenage years to take teeth out and put braces on, but the ADA now recommends assessment and development starting as early as age 7. “By helping kids grow out of the problem, we can ensure fewer adults suffer the implications of sleep disorders—and a shortened lifespan [by] about 10 years—later.”

This, perhaps, is exactly what Dr. Tucker’s patient, Sue Peters, had realized when she presented him with his gift and thanked him for his gift to her: getting her life back.

“I used to have an oxygen level of about 78 at night,” Peters says. “With the CPAP I got maybe 90, and with my OAT it’s now 98 to 100. I’ve been using it for eight years, and it gave me so much more energy. Now I say that [age] 73 is just a number.”

Mellanie Perez

MELLANIE PEREZ is a journalist in Houston. She last wrote for Incisal Edge about the 32 Most Influential People in Dentistry.