Labor shortages aren’t just affecting hygienists—dental assistants, too, have never been scarcer nationwide. Low pay, low morale and a lack of formal certification standards are contributing to widespread burnout, with big effects on practices’ bottom lines. Is the industry past the point of no return, or can this unheralded yet vital occupation be invigorated anew?

By Jerry Markon

NOT SO VERY long ago, things ran smoothly at the Middlefield Family Dental clinic in Middlefield, Ohio, a rural, heavily Amish area about 50 miles east of Cleveland.

The dental assistants made sure of that. There were three of them. They helped the dentist chairside, sterilized equipment, worked the front office and did all manner of other tasks to keep the practice humming.

If an assistant left, a couple of résumés from qualified applicants showed up soon. “I didn’t even have to advertise. They just came in,” says Guinevere Juckett, who doubles as a dental assistant and office manager.

Today, the crisis has abated somewhat—yet the office has just a single full-time assistant, and the dentist, Dr. Amir Shaibani, has stopped seeing new patients. “I can’t tell you the last time a résumé came in,” says Juckett, 51, whose staff is trying to compensate by working smarter.

Juckett is the embodiment of a growing yet mostly unpublicized problem: a nationwide shortage of dental assistants that experts say is expected to worsen. Fueled by a feeling among many assistants that they’re underpaid and undervalued—a sense enhanced by the pandemic—the shortage has led to assistant burnout and to dentists assuming more responsibilities and turning away patients, causing some practices’ revenue to decline.

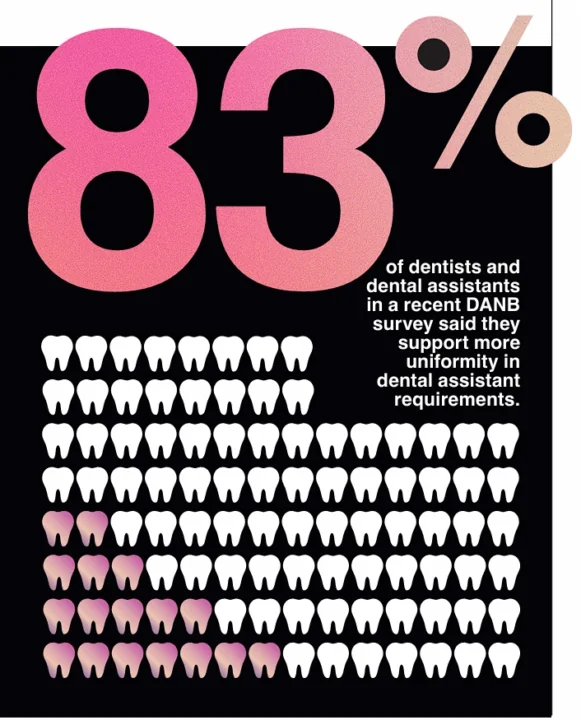

More than 90 percent of dentists across the U.S. reported some degree of difficulty in hiring qualified dental assistants, according to a late 2023 survey by the Dental Assisting National Board (DANB), the certification organization for assistants. Combined with a similar dearth of hygienists (see “The Great Hygienist Shortage,” Incisal Edge, Summer 2024), the assistant shortfall has reduced dental practice capacity nationwide by an estimated 10 percent, according to a 2022 workforce report issued by DANB, the American Dental Association and other groups. “The dental sector is facing a serious workforce shortage,” it concluded. (The other major industry trade group for assistants, the Washington, D.C.–based American Dental Assistants Association, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Looking ahead, the picture appears grim. Roughly

one-third of dental assistants plan to retire within five years, the 2022 report said, while other DANB data show that job satisfaction among certified assistants, while still relatively high overall at 66 percent, has declined more than 20 percentage points since 2016.

As more people leave the profession, far fewer are entering. The number of graduates of dental assistant education programs declined 41.3 percent from 2012 to 2022, according to the ADA’s Health Policy Institute. Over the same period, dental school graduates increased 28.7 percent. Experts say enrollment is not expected to rebound anytime soon.

Before, I didn’t even have to advertise-applicants just came in. Now I can’t tell you the last time a resume came in.

“We don’t have any uniform standards to make us a recognized profession,” Varney says. “You have to go to a licensed dog groomer to have your dog shampooed, yet a dental assistant does not have to get licensed?”

DENTAL ASSISTING dates to 1885, when New Orleans dentist C. Edmund Kells hired his wife, Florence, to help at his practice, DANB records show. Assistants became more common by the early 1900s, and their role has evolved in the century-plus since.

While someone can become an entry-level dental assistant with no specific education, DANB now offers seven national certifications for those who want additional formal training, some of which are recognized or required by several states. Assistants with what is known as “expanded functions training” can perform many of the same tasks that dentists used to do themselves, such as taking impressions and applying fluoride, depending on the state.

At every level, dental professionals say assistants perform vital functions that include greeting patients and setting up operatories, aiding dentists, ordering supplies and helping with charting.

Despite their importance, the shortage of dental assistants has been building over the past decade. Experts say it is difficult to quantify given that not all states require assistants to be registered or licensed, but is generally worse in rural and lower-income areas.

Ironically, Rishel experienced the shortage last year as a patient: Her procedure for a crown preparation was delayed several months because

the dentist lacked the services of an assistant. “Luckily, it was not urgent,” she says.

Some dental assistants can make more working fast food. My son makes $16.75 an hour at Chick-fil-A, and I know assistants making $15 an hour.

THE SHORTAGE of dental assistants was exacerbated by the pandemic, which led many longtime assistants to leave, experts say. Research from DANB and the ADA, though, illustrates more basic, ongoing causes that might well be trickier to solve: Dental assistants are hourly employees who are not paid a living wage and often lack benefits such as health insurance or paid sick leave. Assistants say that has left many feeling underappreciated, with the additional workload brought on by the shortage causing burnout.

While the average noncertified dental assistant earns $22.50 per hour, they can make as little as $15 in some areas, according to a 2024 DANB survey. Certified assistants average $26 per hour.

“The messages I get are heartbreaking,” says Varney, the New York assistant and educator who has made it a point to keep in touch with hundreds of dental assistants. “Some dental assistants can make more working fast food. My son makes $16.75 an hour at Chick-fil-A, and I know assistants making $15 an hour.”

The consequences of the shortage are stark, for practices and assistants alike. DANB and ADA research over the past several years shows that assistant vacancies can lead to canceled and rescheduled procedures, fewer patients seen and significant revenue loss.

It also cites many dentists reporting that they now perform duties typically done by assistants, hygienists or office managers. “We’ve heard many say they cannot run their practice without a dental assistant,” says Laura Skarnulis, DANB’s chief executive officer.

Patel, the dental assistant in South Carolina, was formerly a dentist in his native India. He says doctors are responding to personnel shortages by doing the occasional procedure such as simple fillings by themselves. Overall, that can often take twice as long. “Many practices are limiting the number of patients they see,” he laments. “It directly

affects revenue.”

Practices that are light on dental assistants likewise report an atmosphere that can occasionally seem almost chaotic, where the smooth collaboration between dentist and assistant known as “four-handed dentistry” starts breaking down. “When you are short-staffed like we are, it’s almost double the work for the assistants,” McNally says. “You do a lot of juggling. As a team, you make it work, but it can burn you out.”

We don’t have any uniform standards to make us a recognized profession. You have to go to a licensed dog groomer to have your dog shampooed, yet a dental assistance does not have to get licensed?

IN SAN ANTONIO, Sandra L. Garcia Young has avoided the shortage in part by valuing her assistants. Garcia Young, 46, who oversees assistants and is practice administrator at a CentroMed community health clinic, pays competitive salaries, even doing a salary analysis every few years to stay current.

Her clinic also offers signing bonuses and opportunities for merit pay increases. “When assistants see we are taking care of them, they want to help provide quality care for patients,” she says.

Garcia Young’s efforts symbolize how experts say practices should strategize around recruitment, hiring and retention: Offer competitive salaries, higher if possible, in addition to consistently providing health insurance and other benefits. “Practices need to make dental assisting a rewarding career,” Patel says. “Some assistants are seeing it as a job, not a profession.” Other ideas that dental authorities suggest: Recruit from local colleges and high schools, offer continuing education courses and provide scholarships and grants to assistant education programs.

As practices try to hire and—crucially—keep them, dentistry veterans say assistants should leverage their own value in the market by seeking more education and training, networking with colleagues, picking a specialty and even advertising their services on dental websites.

“Just coming off the street and becoming a dental assistant, you’ll have lower pay and lower value. But by getting your radiology license, you will advance your career,” says Alexis Delaughter, a former dental assistant who now teaches in the dental assisting program at Central Penn College in Summerdale, Pennsylvania.

Even as they contend with marketplace rigors, assistants generally say they appreciate the jobs they have, issues aside. “There is never a dull moment, and what I most enjoy is helping people,” says Juckett, the Ohio assistant and office manager who is wrestling with the shortage.

She has spent 34 years at the same practice, through different ownership. “I would do it all over again,” she says. “I just wish more people could embrace this profession as I have.”