SprintRay’s compact Midas turns up the pressure on 3D printing—literally.

SprintRay’s compact Midas turns up the pressure on 3D printing—literally.

“CERAMIC 3D-PRINTING resins—the kind you’d want to use to print a composite restoration—are viscous, like toothpaste. It’s almost impossible to print them using the conventional gravity-feeding method,” says Amir Mansouri, Ph.D., cofounder and CEO of SprintRay.

So his company set out to make the impossible possible. Using innovative Digital Press Stereolithography technology, Midas leverages a new patented resin capsule system that allows it to print with highly viscous resins previously unworkable with 3D printing. Here’s how it came to life.

Possible vs. Practical

In theory, you could operate a ski resort in searing-hot Scottsdale, Arizona, but it would require a lot of costly

adaptations. That’s kind of like the problem SprintRay faced with early ceramic 3D printer prototypes. Conventional 3D printers rely on gravity to feed material into the build area, a process that works well because flowable resins fill voids like water. Ceramic resins, however, are thick and need to be mechanically moved into place. “If there was a way to build the functionality onto an existing product like Pro S or Pro 2, we would have,” Mansouri says. The company did experiment with a prototype that required a complex spreading and mixing apparatus but could not overcome its speed limitations or need for extensive maintenance. Solving the engineering challenge meant starting with a blank slate.

Secret Lab

Competition is a blood sport for tech companies, which adds significantly to the difficulty of developing genuine breakthroughs. In theory, a companywide, all-hands-on-deck approach to product development would yield the highest number of new ideas—but it would also increase the risk of information leaks. Enter Jing Zhang, Ph.D., SprintRay’s cofounder and CTO. “We kept the project as small as possible. We knew it had to remain under wraps until the patents were filed,” he says. “Since Midas is an in-house product, any vendors we worked with for parts or other sourcing were provided with only the information they needed.”

Ingenious Solutions

With the team assembled, the SprintRay team set to work—with the added pressure of an entire industry biting at their heels. “We were trying to solve the right problem,” Zhang says of his earlier efforts, “but we just didn’t have the right tools.” Then it hit them: What if they could distill the build platform, tank and material into an integrated, single-use part? “That first sketch changed things. Once we had the idea to use hydrodynamics, the product changed very little because it was such a focused, singular device.”

They call this method Digital Press Stereolithography, or DPS, which uses a vacuum-sealed cartridge to replace separate build platforms, tanks and material. Instead of relying on gravity to pull the resin down, the material is pressed and dispensed into the build area, where hydrodynamic principles push the build platform up as it cures. Plus, because the entire printing apparatus is replaced with a new one for each job, “Midas is straightforward and requires virtually zero upkeep,” Zhang says.

Instead of relying on gravity to pull the resin down, the material is pressed and dispensed into the build area, where hydrodynamic principles push the build platform up as it cures.

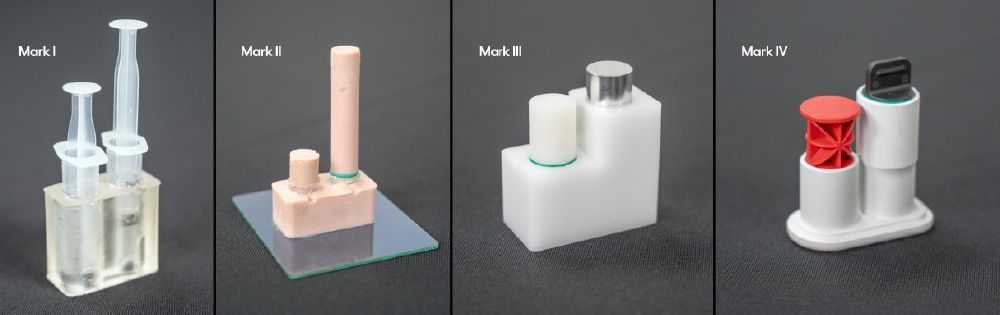

OLD CHALLENGES, NEW CHALLENGES: “Much of the work to prepare Midas for production was learning how to manufacture the resin capsules at scale, reliably,” Zhang says. His team went through four major prototype iterations before finalization.

FROM ROUGH SKETCH TO SUBLIME DESIGN: “Though SprintRay follows “a strict philosophy that form follows function,” according to Mansouri, its products nonetheless exhibit undeniably high aesthetic and tactile appeal. (Above) Cofounder and CTO Jing Zhang in the lab, and early design ideas.

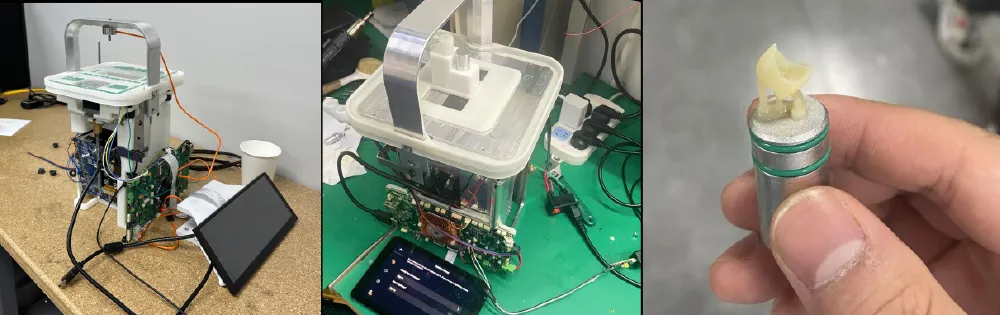

THRILL OF THE HUNT: Mansouri says that “chasing shiny things” is a common hazard for tech companies, so “if it doesn’t provide direct value to our users, we don’t get distracted by it.” (Above) Development of SprintRay’s DPS technology and an example of the prototype’s early output.

NEARING THE FINISH LINE: “Improvements in accuracy and repeatability are a welcome knock-on effect of solving the viscosity problem,” Zhang says. (Above) A Midas prototype going through validation testing.

Materials That Ideally Match

Midas can simultaneously print three ceramic composite crowns in under eight minutes. The unit can also print up to three full-contour crowns, six inlays/onlays or nine ultrathin veneers in a single job. Such a specialized printer

benefits from similarly specialized resins. SprintRay quickly recognized the potential of material partnerships, leading to a recent announcement with Ivoclar. “We didn’t set out with the explicit goal of collaboration,” says Ehsan Barjasteh, Ph.D., head of the SprintRay Biomaterial Innovation Lab. “But Ivoclar is a titan in the materials industry with an incredible portfolio of products and a history of materials excellence. As soon as we had working prototypes, we demoed Midas to them, and the benefits of collaboration were immediately evident.”

Sending prototype units into the field for initial clinical evaluation was risky in terms of secrecy, but necessary. “Clinical assessment is nonnegotiable for us,” Mansouri says. In some cases, that meant delivering a unit to an office for long-term use. In other instances, SprintRay sent a prototype with an engineer for specific use-case testing. “We carefully kept things under wraps before the big reveal at 3DNext,” SprintRay’s annual technology showcase.

Meanwhile, the Midas team was focused on the finishing touches—a process made easier given that SprintRay’s engineering and manufacturing are done entirely in-house. “We follow a strict philosophy that form follows function,” Zhang says. “The goal was to make it as compact as possible because dental offices are notoriously low on counter space. Since Midas doesn’t need a large tank to hold liquid resin, we could shrink the device to its current size.”

Will DPS Replace Conventional 3D?

DPS is outstanding for printing highly viscous resins, like those used for composite restorations, but conventional 3D printing still has many strengths. “They’re highly complementary,” Mansouri says, noting that SprintRay’s other printers are “great for volume production of larger appliances like occlusal guards, removable dentures, models and so on. So these conventional machines still have a clear, high-value use case, and we keep pushing the envelope for what can be done with them.” But DPS paves the way for a whole new set of materials for restorative dentistry. “Since we no longer have to worry about viscosity, our development horizon for DPS stretches far into the future. We see a world where many offices benefit from having both for years to come.”

SprintRay’s compact Midas turns up the pressure on 3D printing—literally.

SprintRay’s compact Midas turns up the pressure on 3D printing—literally.