It’s safe to say dentistry has never seen anyone like Dr. Anne Koch, a renowned endodontist who was recruited to play pro baseball, spent time as a model in Japan, founded a successful clinical department at Harvard… And, at age 63, transitioned from a man to a woman. That last experience led to initial ostracism—but an eventual career renaissance.

AT THE END of Cape Cod’s elbow, down the road from the tony Chatham Bars Inn, in a town surrounded by water on three sides, sits a nearly 250-year-old house that has passed through the hands of ship captains and an Academy Award–winning actress—and now belongs to Dr. Anne Koch.

Dr. Koch, a renowned endodontist and lecturer, bought the house, with four wood-burning fireplaces and wide pine plank floors, in February 2021, in the middle of the pandemic. She loves the home’s antiquity, she says, and purchased it with nearly everything inside it, including one former owner’s collection of antique pewter. However, renovating a house built in 1780 during a historic labor shortage and global supply chain backup has meant prolonged renovation delays as contractors repair aging beams, restore the kitchen’s teak countertops and update one critical detail.

“The kitchen ceiling is six feet, one-and-a-half-inches high,” says Dr. Koch, 72, whose lean, athletic build rises to a height of just under six feet. “If you saw [the house], you’d know why I will persevere. “Listen,” she adds, laughing. “I’m a character. And I’m looking for a house with character.”

Florida woman:

Dr. Anne Koch in her spacious, light-filled

Palm Beach Gardens home. She also owns a Cape Cod house that was built in 1780.

Dr. Koch—pronounced Kotch—is indeed a character, and her stick-to-itiveness has carried her through a life of exceptional accomplishments. An elite athlete who began her dental career in the U.S. Air Force in Japan, she grew to be a leading endodontic practitioner and educator who founded a Harvard residency program. She left academia in her mid-forties to scratch an entrepreneurial itch; she also founded and led a successful education technology company, Real World Endo. After all that, at age 63, Dr. Koch underwent gender reassignment surgery to transition to a woman, the sex she says she had wanted to be her entire life.

Nearly a decade on, Annie, as she’s known—she took the name in honor of her good-natured grandmother, who, she says, seemed to be the only person who recognized that her grandson felt different—runs a consulting business and continues to lecture and donate her time and money to the University of Pennsylvania’s and Harvard’s dental schools.

This year, for the tenth anniversary of the Lucy Hobbs Awards, we’re honoring Dr. Koch with our annual Trailblazer Award to celebrate this unique, pathbreaking figure whose impact on her chosen profession has been simply immense. Her unorthodox journey through dentistry, she says, has taught her many lessons, among them how to build breakthrough programs on a minuscule budget, how developing a simple technique, somewhat paradoxically, requires sophisticated skill, and how to create successful outcomes (both in patient treatment and business) even when you can’t achieve a larger goal.

“I’ve sat at the table as a successful guy and as a successful woman, and it’s very, very different,” Dr. Koch says. “Dental schools, medical schools, you know how competitive everybody is. There are lots of A-types running around, people jockeying for position. My thing is helping students understand and have confidence in who they are.”

The Early Years

Born in Flushing, Queens, on December 20, 1949, to a father who was a New York City firefighter and a mother who was a former professional singer, Dr. Koch says she had a relatively happy childhood, playing sports and spending weekends and summers at the family’s Long Island home.

The family eventually moved from the city to Long Island, where Dr. Koch attended school and excelled at a host of sports: football, basketball, hockey and baseball, among others. She was especially talented at baseball, going on to play varsity catcher at Rutgers University, where she was recruited to play professionally.

My thing is helping students understand and have confidence in who they are.”

In her 2019 book, It Never Goes Away, a memoir she penned about her experience transitioning later in life, she wrote that by age 13, she prayed every night: “God, please make me a professional baseball player or a woman. As it turned out, I had the option for the former later on, but I was smart enough to not go in that direction. Then the other option came true. It is amazing how sometimes prayers are answered.Truman Capote was correct when he said, ‘More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.’ ”

After college, she attended Penn’s School of Dental Medicine, graduating in 1977 and going on to work in private practice for a handful of years before entering the military—an idea suggested by Dr. Koch’s then-wife, who thought it would be a good way to see the world.

Dr. Koch moved to Japan in 1980 for the first of two stints as a general dentist at the Yokota Air Base in Western Tokyo. During her military tenure, which also included a year in South Korea, she would treat tens of thousands of patients, complete more than 20,000 endodontic procedures and perform root canals on six dogs. Perhaps her best story from this period, though, stems from the professional modeling and acting jobs she fell into while there.

“I was in a club one night and one of these Japanese guys came up, gave me a card and said, ‘Hey, have you done any TV or modeling?’ ” Dr. Koch recalls. “I went over, they took a couple of Polaroids, shot a video. In the first week, I scored two editorial jobs and a commercial. That led me to a five-year career as a commercial model and actor in Tokyo.”

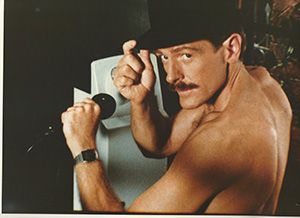

The biggest gig she landed was a starring role in a 1983 Casio watch TV commercial (right), in which she wore a bowler hat, socks, a men’s garter and nothing else. “I was still in the Air Force at the time,” she says, almost blushing but pointing out that the spot became one of the most popular ads of the year in Japan.

The biggest gig she landed was a starring role in a 1983 Casio watch TV commercial (right), in which she wore a bowler hat, socks, a men’s garter and nothing else. “I was still in the Air Force at the time,” she says, almost blushing but pointing out that the spot became one of the most popular ads of the year in Japan.

Her quasi-celebrity and charisma were such that Dr. Koch was often asked to meet and greet visiting Air Force officials. She recalls one encounter that played out at the height of the Casio ad’s popularity. “I was in the front seat of a taxicab, and there were two colonels and a general in the back seat. The driver was a woman, which was unusual for the time. We were going to the Meiji Shrine, but [the driver] wouldn’t let me leave until I signed an autograph.”

To Dr. Koch’s surprise, the general was amused.

“He loved it! He’s thinking, ‘We’ve got a medical officer here who is really enjoying Tokyo,’ and he blurts out, ‘You can stay here as long as you want!’ ” Then comes the punchline: “Andy Warhol said everybody gets 15 minutes of fame. Well, I got four and a half years in Japan.”

Harvard and Real World Endo

In 1990, at age 41, Dr. Koch returned to the United States. Bolstered by a significant amount of clinical experience overseas,

she enrolled in Penn’s endodontic specialty program. “I was the oldest resident in the school,” she says. “I didn’t understand why they were doing certain things a certain way.”

Within a year of getting her endodontic certificate, she was asked to help found Harvard School of Dental Medicine’s postdoctoral endodontics program. “I had a very, very limited budget. If I told you the amount, you would laugh,” she says. “They were looking for a person who realized that I’ve got no money here, but I’ve got a world of opportunity.”

Over the next three years, she averaged 80 hours a week at the school, working to “not create somebody who could do a root canal [but] create somebody who could change the specialty. That put me on the map in endodontics. There was a lot of pushback. The large Boston-based endodontic practices and other nearby schools all felt threatened by Harvard creating a program of its own. I was able to work through the political minefield for this program.”

In addition to learning diplomacy, she says she also took to heart a valuable lesson from a Harvard colleague about how to manage others’ expectations. One particularly taxing day when Dr. Koch felt exhausted running the underfunded program, the colleague advised her to “do what you want to do, feel confident about that—and if it doesn’t work out the way you wanted it to, just be sincere in your apology and nothing will happen.”

The publicity she got for her achievements in Cambridge resulted in a number of professional offers, and in 1998, Dr. Koch moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to take a job as a director of professional services and universities for Dentsply Tulsa Dental.

I may not know how

to do a rib roast, but

I know how to make endo products.”

In Dr. Koch’s mind, this was her chance to get an MBA without going back to school, and she quickly found her entrepreneurial spirit, accompanying colleagues on sales calls and learning how to navigate the patent process.

She started the company’s education platform from scratch and grew it, she estimates, “by 7x” before moving back east to found Real World Endo, a continuing-education company focused on endodontic treatment techniques and technologies. “I may not know how to do a restaurant-quality rib roast, but I know how to make endodontic products,” she says.

The company became a huge success, and Dr. Koch, who is still involved with it as a member of its “faculty,” now holds four patents for endodontic techniques.

A Monumental Transition

While in the back of her mind Dr. Koch had wanted to be a woman, she says, since as early as 4 years old, it took a health scare at age 63 for her to make the difficult decision to take the steps medically to become one.

While in the back of her mind Dr. Koch had wanted to be a woman, she says, since as early as 4 years old, it took a health scare at age 63 for her to make the difficult decision to take the steps medically to become one.

At the time, she was married to her second wife, living between their homes in Long Island and West Palm Beach and working as the chief executive officer of Real World Endo. “For more than 35 years, I was a leading practitioner and educator in my dental medicine specialty,” Dr. Koch wrote in It Never Goes Away, which she penned specifically, she says, for people considering transitioning at a mature age. “I treated over 30,000 patients with compassion and concern, presented over 1,000 lectures worldwide, founded a Harvard residency program in which I helped train dozens of residents and created a successful education technology company.

“This all came to an end when I changed sex.”

The dramatic difference in her appearance (which she thought made her look like her former self’s sister) was a transformation that many members of her family, friends and professional colleagues found overwhelming. She was asked to leave the business she founded, her marriage eventually ended and, paraphrasing a Yardbirds song from the 1960s, Dr. Koch says, “I spent two years going over, upways, sideways, down.”

Then, a sort of deliverance: “What changed was that out of the blue I got an email from the Penn alumni department saying, ‘We noticed you changed your address, and we noticed you changed your name?’ ” she recalls.

She spoke with the alumni representative by phone, and the next day she received an email from Dr. Syngcuk Kim, who was the chairman of the department of endodontics at Penn when Dr. Koch completed the specialty program there in 1993.

“He was very, very difficult as a chair—almost a tyrant,” she says. “He sent me the most loving, humanistic email I have ever received, and [Penn] invited me for something like an unofficial Anne Koch day at the dental school. It was absolutely stunning for me. Penn became my family.”

Dr. Koch says that outreach ultimately laid the groundwork for her to endow Penn Dental School’s second-biggest seminar room, outside of which is a plaque that reads a place to call our own. She donated the gift, she says, in recognition of LGBTQ students, residents, faculty and staff.

“I had never lived my life in that space,” Dr. Koch says, referring to being an out trans woman working or studying in academia. “I could not believe the discrimination, prejudice and angst associated with that in professional schools. I found it appalling.”

In the years since, she has endowed a five-year program on transgender health at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, as well as providing support to the diversity-and-inclusion Program at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

She estimates she has given away a quarter of her wealth to these programs and through other assorted gifts to Harvard and Penn, schools for which she happily admits her bias. “With Penn, I’m very happy to do things with them because they changed the game for me professionally. And I’m happy to do this with Harvard because they gave me an opportunity and have been grateful for what I’ve done with it.”

She recounts a favorite phrase of Harvard deans: To whom a lot has been given, a lot is expected. She says she is happy to “step up and provide a model.”

And while she exults in the letters she gets from dental and other medical professionals who have read her book, she’s most enthused about the younger clinicians working to make the profession more equitable: “I’m a person who thinks every generation is bigger, better, brighter, smarter.”

“I’m a person who thinks every generation is bigger, better, brighter, smarter.”

ELIZABETH DILTS MARSHALL is a regular contributor to Incisal Edge.